taly’s Salvini Rises, With Fiery Words and Pragmatic Decisions

Posted by hkarner - 14. Februar 2019

Date: 13-02-2019

Source: The Wall Street Journal

Interior minister, head of the ruling League party, has become a central figure in efforts to build a pan-European alliance of nationalists and nativists

PIANELLA, Italy—Far-right lnterior Minister Matteo Salvini strolled through a crowd of supporters in the main square of this southern Abruzzo town. Leaping on stage to campaign for regional elections, Mr. Salvini took aim at prosecutors who have charged him with kidnapping 177 African migrants last year after he refused to let them disembark from a rescue ship.

“They will have to put me on trial for the next 20 years, because I’ll go on blocking the migrants ships,” Mr. Salvini told the cheering crowd last week. “If they think they are scaring somebody, they chose the wrong person.”

In practice, though, Mr. Salvini is working to preserve his immunity against prosecution as a member of Italy’s Senate. His electioneering effort worked. On Sunday, a far-right candidate for governor backed by Mr. Salvini’s League party won the Abruzzo election.

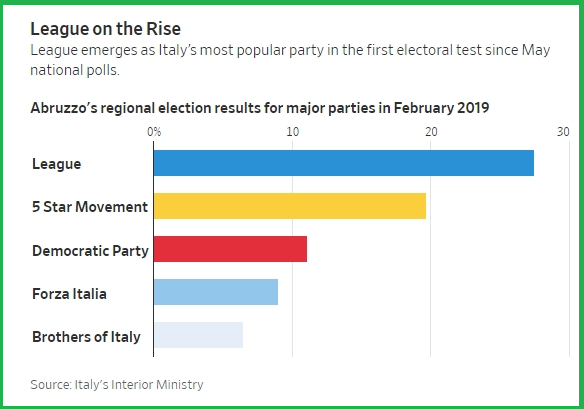

Mr. Salvini is one of the fastest-rising politicians in a major European Union country. He has turned the League, a moribund regional movement in Italy’s north, into the nation’s most popular political force. His combative anti-immigration rhetoric and down-to-earth persona on social media have tapped anger at Italy’s aloof, ineffectual political establishment in swaths of Italian society.

A look at Mr. Salvini’s decisions in power suggests he is more of a pragmatist than his rhetoric implies.

Next, he says, he wants to take the EU by storm in this May’s European Parliament elections. He has become the central figure in efforts to build a pan-European alliance of nationalists and nativists, including politicians such as France’s Marine Le Pen and Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orban. It’s unclear, though, whether Europe’s disparate far-right parties can unite, and what their aims would be.

Mr. Salvini, a bearded 45-year-old former journalist, has built his rise on the image of a revolutionary chief, or “the Captain,” as his devoted fans call him. In recent years he has promised to overthrow Rome’s rotten political class, to split Italy’s richer north from the rest of the country, and to take Italy out of the euro.

But a closer look at Mr. Salvini’s decisions in power suggests the open-shirted former college dropout from a gritty working class part of Milan is more of a pragmatist than his rhetoric implies. That has implications for the EU if Mr. Salvini’s rise continues.

Since the League took over Italy’s government last June, in coalition with the antiestablishment 5 Star Movement, Mr. Salvini has dropped his anti-euro rhetoric, watered down his expensive tax and pension promises, and said he wants to reform the EU from within, not to leave or destroy it.

“His agenda is clearly pragmatic,” said Alessandro Franzi, a biographer of Mr. Salvini. “When he needs to decide on specific matters, he is very practical and leaves the political ranting behind.”

His mercurial behavior also reflects the League’s complicated character. Despite its sometimes radical talk, it is also the longtime governing incumbent in the wealthy industrial heartlands of northern Italy. Its base includes thousands of entrepreneurs who would like lower taxes but who don’t want disruptive experiments such as withdrawal from the euro.

“The League’s typical voters are very angry people, but who are well-off and have a lot to lose economically,” said Giovanni Orsina, a history professor at Rome’s LUISS University. “It’s an electorate that demands radicalism in rhetoric and realism on practical choices.”

Ahead of national elections in early 2018, Mr. Salvini decided to drop the League’s yearslong quest to quit the euro, saying it “was no longer the time” to do it.

Last month, he also backed the bailout of ailing bank Banca Carige SpA, despite having blasted previous governments for similar bank rescues.

Last month, he also backed the bailout of ailing bank Banca Carige SpA, despite having blasted previous governments for similar bank rescues.

The interests of the League’s business supporters were the key to Mr. Salvini’s decision last fall to de-escalate Italy’s budget spat with EU authorities. Brussels had protested against the new Rome government’s plan to increase Italy’s budget deficit significantly, breaking EU rules that required reducing the deficit. Investors, worried about tensions between the EU and heavily indebted Italy, dumped Italian government bonds, hurting Italian banks and pushing up the cost of credit for Italian businesses.

Mr. Salvini sharply attacked EU officials early on in the dispute. But by late last year, he had quietly dropped his promises to introduce a flat-rate income tax and rip up past governments’ pension reforms. Instead, he sold incremental tax and pension changes as the fulfillment of his campaign promises. His approval ratings suggest voters didn’t mind the climb-down.

Stefano Di Donato, who backs Mr. Salvini, says migrants ‘can’t expect to enter a country based on a sense of entitlement.’

“We are starting to do things. The League is different because of facts: We do things, we leave the chitchat to others,” said Mr. Salvini at another rally in the tiny town of Bussi sul Tirino.

In keeping with his man-of-the-people image, Mr. Salvini campaigned in the mountainous Abruzzo region wearing jeans and a ski jacket, eschewing the fine tailoring of Italy’s traditional political elites.

“He is one of us. He speaks like ordinary people. We can address him as Matteo, not Signor Ministro,” Erika Mioli, a 43-year-old office clerk, said after she queued for a selfie with Mr. Salvini.

Stefano Di Donato, an 89-year-old former immigrant to the U.S. who returned in his native Abruzzo in retirement, said he agrees with everything Mr. Salvini says about illegal immigrants. “When you go to work abroad, you go legally, like I did! You can’t expect to enter a country based on a sense of entitlement,” Mr. Di Donato said.

“We are changing Italy, and after liberating Abruzzo, we will change Europe. We’ll kick out all these bureaucrats,” Mr. Salvini shouted at a raucous crowd at his final rally of the day.

Hinterlasse einen Kommentar